One of many apparitions in Tony Kushner's Angels in America, an 18th century dandy paying visit to a sickly descendent, observes with bemused dismay having arrived in 1985 New York, "The twentieth century! Oh dear. The world has gotten so terribly, terribly old."

Like most ghosts who show up in plays, he knows what he's talking about. The world has become disturbingly antique--it's just that parts of it have a trick about seeming more decayed than others. The United States (if only in stodgy, post-colonialist nation-state terms) is still hardly more than a toddler, wobbling down the transglobal sidewalk on chubby legs and dropping its pacifier in the mud. Compared to a more mature Western country like, say, England, it's got about as much historical depth and baggage as last week's episode of "Wife Swap." The difference is a rich English heritage but also a punishing debt, legacy, and accretion of guilt; that is to say, the weight of a collective national onus more than a thousand years in the making. Imagine what living in the U.S. might be like if it'd been suffering fools and faking wars since 876 rather than 1776.

When Queen Elizabeth I travels into the future to discover her kingdom's destiny in Derek Jarman's Jubilee, she finds an apocalyptic post-Britain driven mad by its terrible oldness. Gangs of girl-Londoners go on public rampages of torture and murder, heaps of rubbish burn seemingly nonstop, and political power has all but yielded to a creepy, bald media impresario called Borgia Ginz. Ginz is perhaps meant to recall the ruthless Italian Renaissance family and mobster collective of his first name, and Jack Birkett, with his bugged-out eyes, maniacal giggle and meth addict's leer, plays Ginz as a kind of queeny, arachnid Cesare Borgia fully prepared to enjoy the benefits of his self-made autocracy. He is orbited by a duo of mute lady supermodel-types (rather unconvincing given the way he ogles Adam Ant) as well as the terrorist gang whose bickerings and crime sprees make up much of the film. Leader Bod (Jenny Runacre), sadist Mad (Toyah Willcox), nympho Crabs (Nell Campbell) and cynical historian Amyl Nitrate (Jordan) share a dingy bunker of an apartment and go on group trips to the corner chip shop to kill the cook.

In the end, Jubilee narrowly misses being a radical feminist film. Its leading female characters seem driven by a righteous, primal rage, as if the accumulating centuries of gender inequality have finally taken their toll and inspired the women of England to take to the streets. Mad ridicules Crabs for sleeping with men, spitting, "Sex is for geriatrics!" and carves the word LOVE into Bod's back with a knife. Viv, a peripheral member of the gang, is having a giddy three-way with two brothers (Angel and Sphinx, who are also happily doing it with each other), and everybody is a prickly, beauty-fucking, androgynous mess. It's a shame, then, that the majority of the gang's victims are women, and not just biological ones. Wayne County has a few seconds of prancy karaoke screentime before Mad and the girls arrive to push her about, shove her to the ground and throttle her to death. Mad's satisfaction in the murder appears to arise from something akin to transphobia, and the scene mimics too many other on-screen tranny-killings in which the perverted she-man is left splayed on the floor, wig torn off, and exposed for the fraud she really is.

Similarly, Angel and Sphinx's deaths at the hands of the police, though granted an emotional gravitas and tragedy rare in the rest of the film, are instigated by Angel's blithe come-on to an approaching officer, "Give us a kiss!" Jubilee has (bizarrely) drawn criticism from some for being politically conservative, and this is the only place in which such a reading holds water; by presenting sexual freedom side by side with corruption, looting and murder as an effect of a crumbling society, the film implies that queerness might not have a place in the reformed utopia for which it longs.

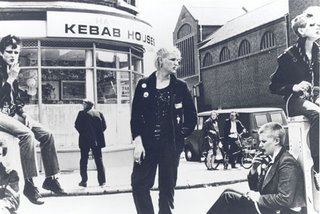

Running through Jubilee like a Manic Panic'd neon pink stripe is the first-wave punk aesthetic that insiders like Vivienne Westwood feared the film would exploit. She needn't have worried; the fashion and music on display bristle with authenticity, and Jarman gets it right. Adam and the Ants turn in a scalding performance of "Plastic Surgery" (note the pointed anti-exploitation, anti-music biz commentary that follows the song) and a decidedly un-skinny Amyl sexes up "Rule Britannia" with snap garters and grrrl snark that foreshadow Corinne Burns in Ladies and Gentlemen, The Fabulous Stains. Like Corinne's, Amyl's trashy rent girl stage persona is an escape ladder out of her oppression rather than an effect of it, even as the flat tone of her "sexy" posturing suggests a behind-the-scenes male puppetmaster, controlling her movements, options, and body-as-commodity.

Jarman's interest in gender and British social history informs a Warholian understanding of the pop star as artificial, irresistible,and a little bit toxic. Ginz's pet musicians (engineered with Malcolm McLaren-like cunning) have lost control of their careers before those careers even begin, giving themselves up to an increasingly deranged popular culture in which art is dead but Top of the Pops is always on. "The world is no longer interested in heroes," Mad tells us. "We now know too much about them." And what are pop stars, if not heroes who've been interviewed in Vanity Fair one too many times? As Jubilee concludes in a last gasp of violence and grief, it becomes painfully obvious that its plea for compassion and realness originates not in a parallel universe, but our own.

No comments:

Post a Comment